Knut Ivar Aaser, Nicolas Ceccaldi, Ida Ekblad, Tatjana Gulbrandsen, Eckhaus Latta (with Alexa Karolinski), Matthew Linde, Mathieu Malouf, Roland Penrose, Kier Cooke Sandvik, Kjartan Slettemark, Rita Westvik

Curated by Eirik Sæther. Exhibition text by Stian Gabrielsen.

Unshelling and Shelling Again quotes a caption from a YouTube-video where a hermit crab is coaxed, through incessant tapping, to exchange its original shell for one carrying an imprint of the cartoon character SpongeBob. The video, made by kids who you can hear laughing off camera as the flaccid and vulnerable crustacean finally gives in to his tormentors and exits his former home to take up residency in his new, could well have been included in the exhibition. Crawling frightened up into its SpongeBob-emblazoned abode the crab represents an apt instance of the kinds of flamboyant performative practices that Unshelling... presents.

The absence of artistic intention on behalf of the makers of the video

Knut Ivar Aaser, Nicolas Ceccaldi, Ida Ekblad, Tatjana Gulbrandsen, Eckhaus Latta (with Alexa Karolinski), Matthew Linde, Mathieu Malouf, Roland Penrose, Kier Cooke Sandvik, Kjartan Slettemark, Rita Westvik

Curated by Eirik Sæther. Exhibition text by Stian Gabrielsen.

Unshelling and Shelling Again quotes a caption from a YouTube-video where a hermit crab is coaxed, through incessant tapping, to exchange its original shell for one carrying an imprint of the cartoon character SpongeBob. The video, made by kids who you can hear laughing off camera as the flaccid and vulnerable crustacean finally gives in to his tormentors and exits his former home to take up residency in his new, could well have been included in the exhibition. Crawling frightened up into its SpongeBob-emblazoned abode the crab represents an apt instance of the kinds of flamboyant performative practices that Unshelling... presents.

The absence of artistic intention on behalf of the makers of the video would not pose as a curatorial challenge in regards to the show. More accurately, perhaps, would be to replace the term “practices" with “behaviours", as being the result of a typically reflective artistic process is not a criterion for the selection of work included in Unshelling.... Our crustacean in the YouTube video would well be interpreted as performing in the same vein as the artists, designers, directors, entertainers and models that contribute to the exhibition. What inspires the crab to change his wearables is not some intentional engagement with the the codes of representation, but rather a subpersonal response system—fleeing from what he is hardwired to perceive as a threat.

Used as a tentative framework for making sense of the exhibition, the unshelling-event sheds doubt on the assumed causal relation between art and intention. On such a post-intentional account, Unshelling... is curated by a selective procedure that tracks behavioural similarities across a large archive of images, regardless of what sort of social practice engendered the behaviours in the first place. The absence of any realtime performances—we're only privy to these extravagant behaviours via documentation in the form of videos and photographs—also testify to the levelling at work here. The title, which initially describes a crab leaving its shell for a new one, can be reduced to a simple algorithm: out (unshelling) and in (shelling), which roughly correspond to a switching between appearing and withdrawing, flashing and hiding.

Speaking through various media, most of the contributors on some level combine social seclusion or invisibility with moments of expressivity or carnevalesque “going out". The word “shelling" can also be taken to mean artillery fire or bombardment, alluding to the often confrontational nature of this “going out".

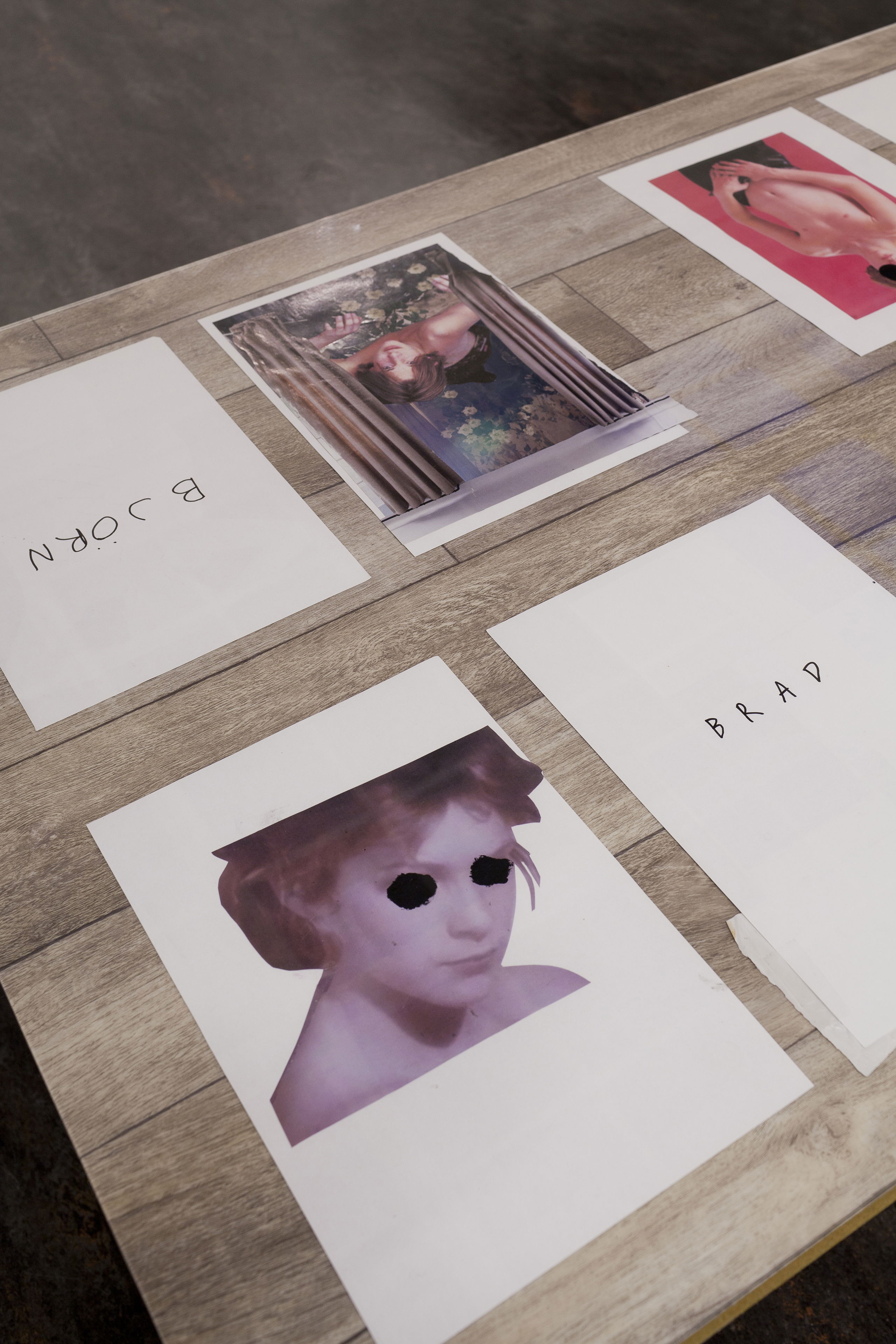

No one takes the confrontational cue further than Lars Kristian Gulbrandsen (1931-2005) who at the age of 70 recast himself in the role of the 23 year old girl Tatjana Gulbrandsen, donning pigtails, crop tops and miniskirts, and before that had cultivated a decade-long habit of covering his face and body with thick layers of house paint. Coupled with outlandish transvestite creations, this get-up had, unsurprisingly, ensured Gulbrandsen a high level of visibility in the small town of Flekkefjord. The house where he spent the last 40 years of his life is now a defunct, untended-to museum, where the hundreds of photographs chronicling his life-long contrariness, as well as sculptures, paintings and decorated furniture are stored.

Though trained as an artist and painter, Gulbrandsen is a hard case to reconcile with an image of the artist as someone attuned to the demands of building a career nested in the nervous spiderweb of professional life. His art is local, both in terms of his physical involvement with the materials (he wears them) and in the way his work is inseparable from the interaction with the residents of Flekkefjord. Creation and crafting of identity is a communal enterprise—a sequence of portraits among the many on display in Unshelling... was typically a result of an arrangement with the local photographer who would offer up his services for free. In the same spirit the local hair salon, after Gulbrandsen was encouraged to stop using house paint on his body for medical reasons, treated him to make-up sessions in between paying customers.

If behavior rather than artistic intention is what Unshelling... surveys, this would explain the prominent inclusion of a photo of the British army's former camouflage expert Roland Penrose's wife, posing in what could be described as a tongue in cheek send-up of Manet's painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. The photo was taken during a session where Penrose used her to model his camouflage techniques. In the picture presented at Kunsthall Stavanger, naked and painted green, seated among her husband's male colleagues during an intermission, she not so much melts into the landscape as demonstratively broach her feminine presence. Transplanted from the natural surroundings that her green make-up is meant to mimic to the social setting of a picnic, her camouflage changes into a means of standing out. The simple switch whereby explicitly adaptive behavior, wearing camouflage—or modelling it for educational purposes (the series' irrepressible crypto-erotic theme aside)—take on the air of social provocation, and speak to how considerations of context are decisive in deciding when behaviours become performative.

Kjartan Slettemark's early work was frequently of a socially confrontational bent. The performance-documentations shown in Unshelling... are from the latter part of his life, after Slettemark had consigned himself to produce art in a more affirmative vein, centred around aesthetic rather than political concerns. As such, while still infused with the same eccentricity as before, these staged events are not equipped with the goal-directedness of transgressive political action; they exemplify a diffusion of political agency into a muted celebration of meaningless (though not necessarily pointless) creative activity.

This art-as-attitude was always a credo in fashion, as evidenced in the video documenting two models showcasing Eckhaus Latta creations. (The video was made by the designers in collaboration with Alexa Karolinski.) Here, the catwalk is folded into the utilitarian and mall-like atmosphere of a Home Depot, thus aligning the self-aware posturing and prancing of fashion models with the mind-absent goings-about of shop clerks and customers.

Da jeg var hest (1986) is a music video directed by Rita Westvik, based on Elsa Kvamme's cabaret performance of Jaques Brel's Le Cheval. In Westvik's rendition, Brel's lament of the loss of horsehood (“I was really (...) a lot happier before when I was a horse") becomes a means to map a woman-performer onto a galloping horse. Where Brel's lyrics complain about the travails of bourgeoisie life and long for the days when he was unconcerned with manners, a horse, Westvik's playful surrealism and acrobatic choreography—embodied in the theatrical costumes as well as dance moves and her 80's template of crude, analogue montage techniques—portray Kvamme's outgoing performance as a cut-up stampede that rip through the representational regimes of marriage, wall-hung art and exhibition openings.

Also of note is how the video-montage, being the means with which the protagonist's yearned-for regression is realised, paradoxically suggest that the return of (wo)man to nature is achieved with the help of technology. The notion broached here, that technology offer a way of naturalising human subjectivity, echoes the way the curatorial method at work in Unshelling... suggestively return performance to the more general category of behaviour, to something that can be parsed within a causal schema.

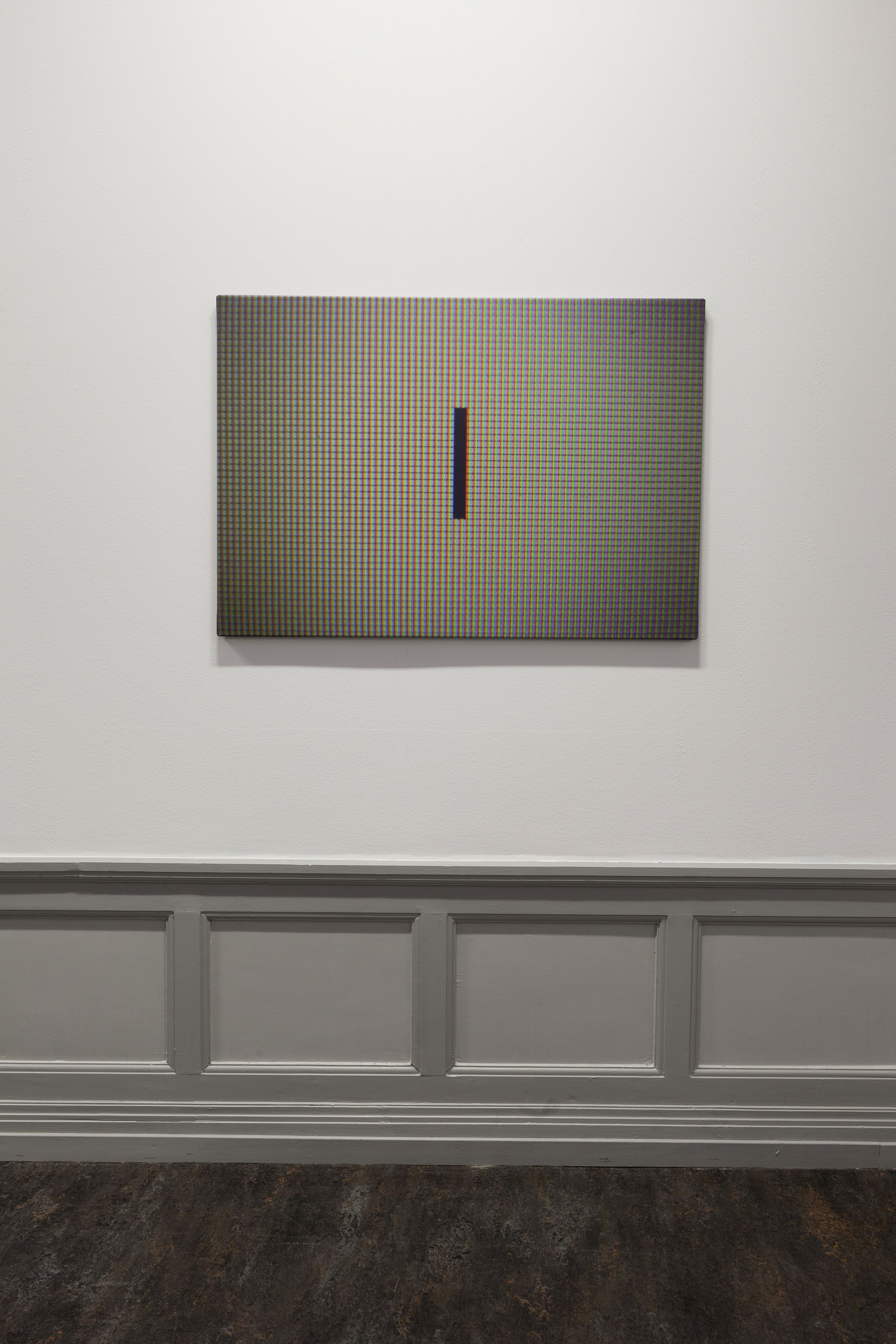

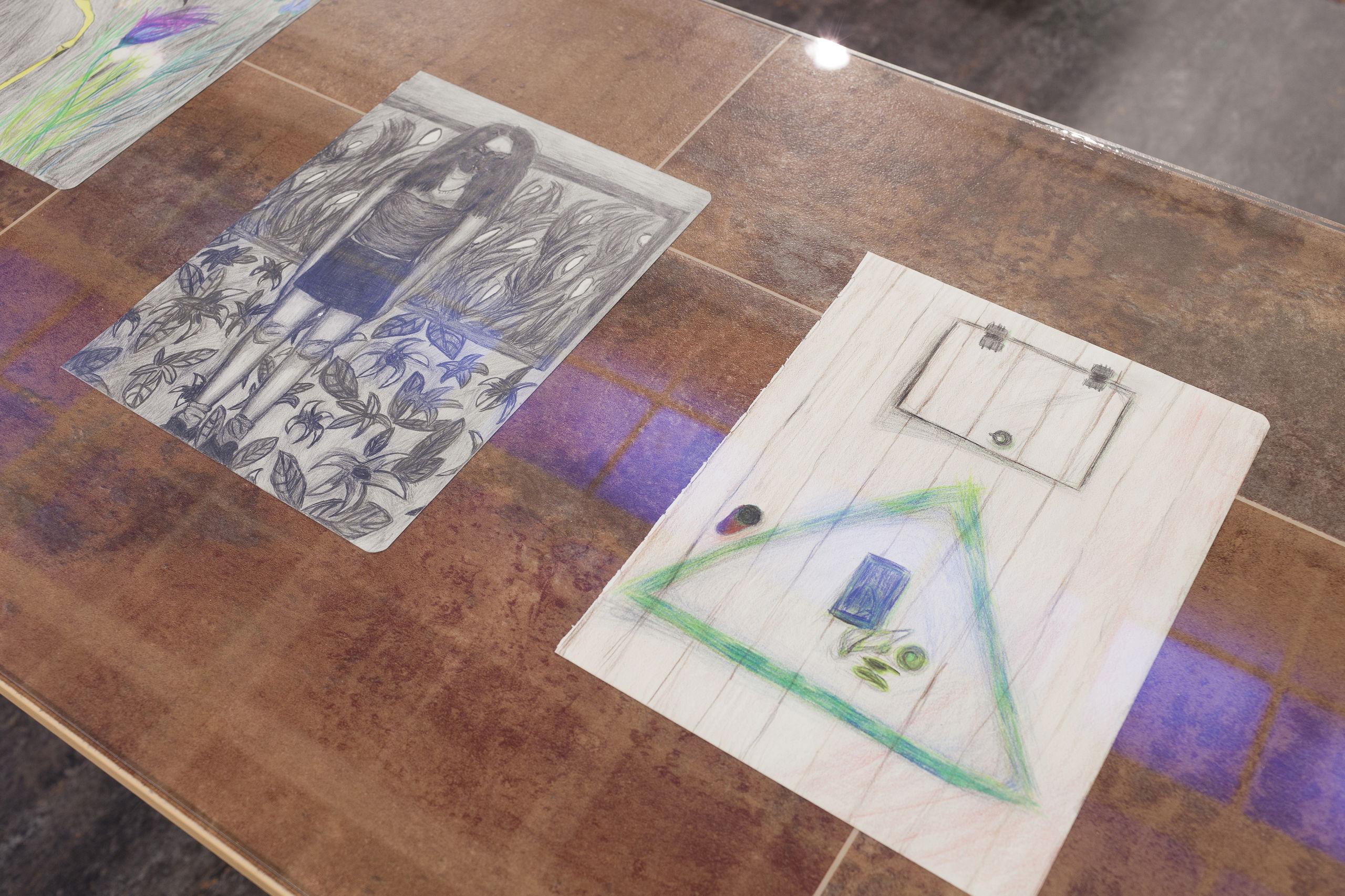

Perhaps this growing transparency of our selves to ourselves (and even more so to the algorithms that do the mapping) is what is adressed in the digital print by Nicolas Ceccaldi, where a lonely, void “I"is all that remains uncharted in an otherwise luminous, pixelated field—the same “I" we find incessantly invoked and then lost again in the visceral and melancholy drawings, collages and photographs of Kier Cooke Sandvik.

If the first part of the exhibition—with its nearly muted, small-square formats—presents itself as a clinical survey, the second part, comprised of works by Ida Ekblad, Knut Ivar Aaser and Matthew Linde, takes an opposite approach. Instead of offering their work up as separate case studies, they have been welded into a more continuous display format. The room they occupy will also function as a backdrop for a performative work by Linde. Without losing track of the theme of performance as extrovert behaviour, the presentation here is less discursive in tone. If one was to stick with the outlines of the definition mapped above, then perhaps this part of the show could be compared to an operating theatre – or “circus" to borrow a euphemism favoured by the fictional surgeon John Thackery (The Knick, HBO). A place for performance, in other words, for action. In one episode Thackery, in a fit of cocaine induced hubris, believing he has solved the mystery of blood transfusions (the year is 1900, blood types were yet to be charted) he picks out a patient at random, a young girl, and, assisted by his lover, nurse Elkins, wheels her into the operating theatre where he puts her under and commences to give her a transfusion directly from his own arm through a fat rubber tube. The girl, of course, is dead within minutes. “What have I done?" Thackery asks himself after his patient's death has been established—an oft timely question even in situations where you haven't killed someone by forcing your own blood into their body. Experimentation always runs a risk, and one of the pitfalls of performance is the risk of not connecting, of falling flat. Perhaps the theory that undergirded your attempt was misguided, or (more likely) you never really intended to connect with your audience in the first place.

The choreography of Matthew Linde's body during his performances seem attuned to the problem of making contact. Self-consciously dressed up, he nonetheless acts as if he was alone—sloped in a corner singing karaoke (Painted Stain at fucking demure performing “pretty"), or hunched over a slip of paper that he reads from. The story he tells symptomatically map the experience of an intimate grappling with another's physique. Even if it is presented as a first person encounter, the medium of text fictionalises it.

More telling, however, than the unverifiability of the purported encounter, are the physical gestures Linde makes on stage: His forward-leaning, half turned-away body, the gaze tethered to a slip of paper; never once does he turn to or look up at the presumed audience - he hurries through in a subdued voice and scuttles off stage. Often, Linde performs in an environment of his own design centred around assemblages of fashion clothing and accessories. Normally perceived as social instruments, or ways of making the flesh socially presentable, these garments, along with a host of other props garnered from the world of window displays, dressing rooms etc., have a different function in Linde's work; here they are recast as a form of disconnected blood transfusion tubing. He is perpetually stuck in the dressing room, rehearsing his debut.

In his work for Stavanger Kunsthall, the floor houses an arrangement of anthropomorphic sculptures. Various display racks and mannequins have been amended with a mixture of self-drying clay and second-hand clothes. The clothing is partially covered by the clay, making it hard to discern the different garments. Rather than forming a separate layer, or skin, the garments are merged with the “flesh" of Linde's makeshift models. Linde here depicts the body in a morbid state of ingoingness, so to speak, where what hinges it to the representational domain of social interaction is in the process of being devoured by unpresentable flesh.

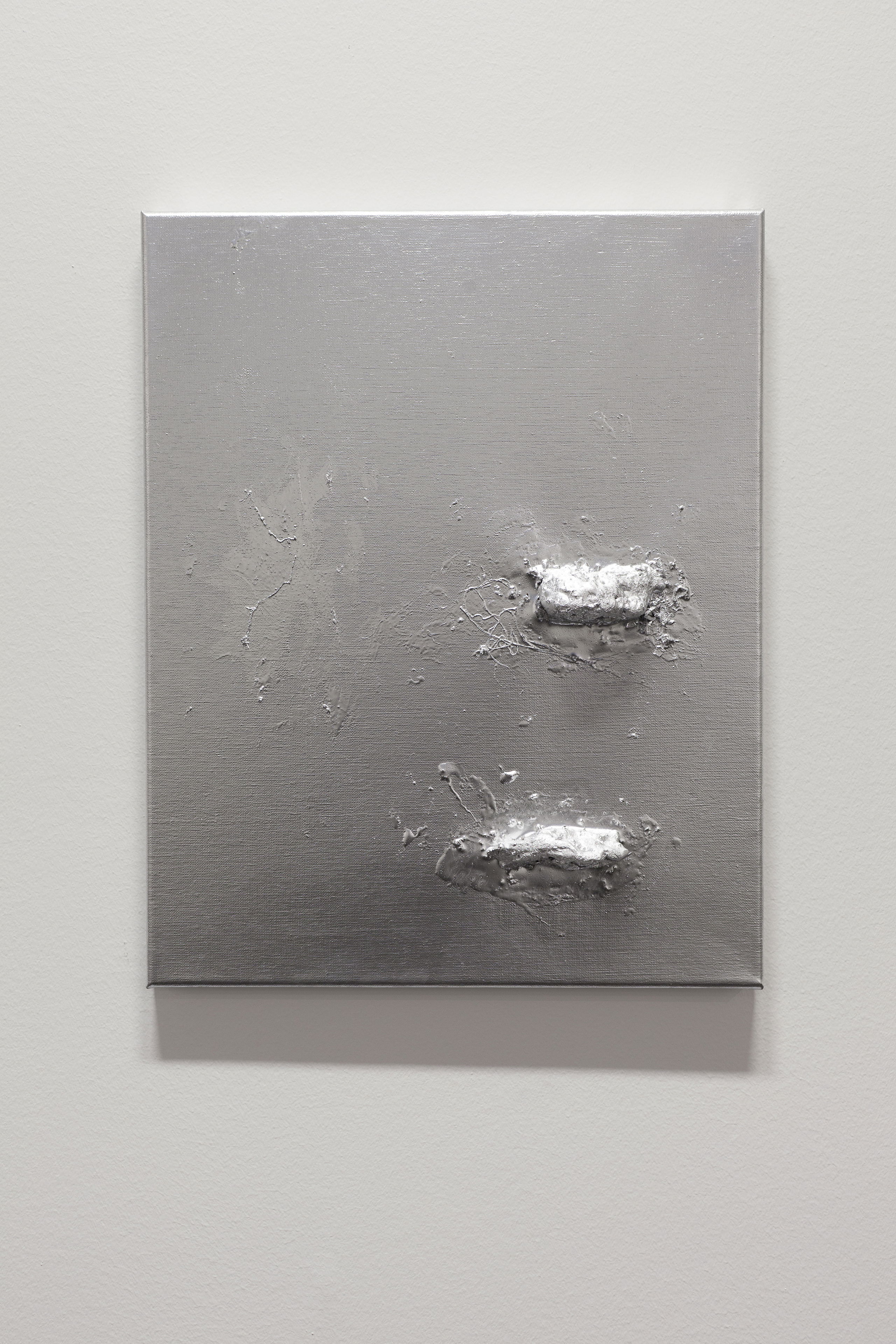

Two out of the three paintings that Ida Ekblad will be showing, carry an imprint of the same disfigured cartoon character. The third canvas simply spells “SADE" in sinuous white lettering on a blue-dyed background and an arbitrary-looking airbrush-painted figure. Although it is endowed with a lax aura, the application of the cartoon and the text nonetheless involve a rather time consuming process – a technique called “puff paint", where a special paint mix is applied to the canvas and then heated. Certain components in the mix react to the heat by expanding and the painted figure grows into a three-dimensional form. In one painting, this reliefed cartoon floats over a skewed chess-board pattern, in the other the background is haphazardly covered with black airbrushing in a shape resembling the one in the SADE-canvas, only denser. In both cases the nozzle has been held close to the support, narrowing its mark to a continuous, rambling line that simply traces movement across the canvas. Used like this the airbrush tool clearly cite the expression of spray cans—a painting utensil associated with the transgressive publicness of graffiti.

The invocation of the French libertine author Marquis de Sade, who in his writing espoused moral scepticism and a ruthless pursuit of desire, tacks this displaced graffiti to a libidinal source. Rather than territorial pissing, Ekblad douses her canvases with “spray paint" gestures at its potential as a site for pleasure and drive. By abiding no discernible rule except the restrictions imposed through the canvas' rectangular shape, the circuitous trail of the “spray can" could be read as a mapping of desire at its most whimsical—simultaneously light and sinister, like hands fumbling over flesh in an attempt to arouse it. The notion of publicness—of going out—associated with grafitti, is here applied to a format that serves as a vehicle for artistic expression—the painted canvas—and thus negotiates the boundary between the private and the public sphere. Despite the laborious technique used to endow it with corporeality, a body to perform with, the drunken cheer of the cartoon function as a gesture towards the death of any attempt at holding it together, at resisting the dissolving effects of desire.

More austere then, are Knut Ivar Aaser's machine knitted noveau-style carpets. If Ekblad's paintings are desirous improvisations that aim to track their own arbitrary becoming—Aaser feeds his drawings through a knitting machine, instead enacting a curtailment of the same drive. His two wall-mounted carpets also echo the persistence of textiles in the exhibition, but in an opposite key than for example Linde or Gulbrandsen. Not only does a carpet have muffling properties in a literal sense—operating the knitting machine requires strict adherence to a certain procedure: a patient and repetitive sliding of the carriage module back and forth. This process ties in with an industrial form of production, and the texture of the knitted surface gives the image a uniform, muted expression.

Though the original act of drawing is casual and free, when the marks emerge on the other end of the knitting process they are transformed into innocuous ornaments. The figure of the machine knit, and its myriad of interlocking masks, evokes the frequently used metaphor of “fabric" in reference to the bounding of people into larger collectives—as in phrases like, “the fabric of society". The knitting here evokes an atmosphere of belonging and being cared for—and of crafting, stocking, feeding, and resting. La det lukte grønnsaker! (Let it Smell of Vegetables!) as Aaser poignantly named one of his exhibitions. The wholesome smell of vegetables, of course, can also get sickening after a while, oppressive even. Which is probably the point—and also why, every once in a while, someone elects to smear house paint on their face and wear a miniskirt, even if it means their balls are showing.