Kunsthall Stavanger is proud to present Bleak House, the first exhibition in Norway by artist-duo Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings. Featuring an installation of 15 found dollhouses and a multi-channel sound piece, as well as a selection of original etchings and a video work, the exhibition highlights the relationship between architecture and the construction of identity, power dynamics and societal norms.

Quinlan and Hastings are London-based multidisciplinary artists working across painting, drawing, video, performance and installation. Their practice is grounded in researching how various communities have been represented at different moments in history as they look to art history and archives to interpret social and political issues facing us today. Amongst other things, they have studied queer environments, explored the impact of austerity, gentrification and policing on urban spaces, and investigated the more overlooked facets of western feminism, particularly its relationship to the political right. Through their work

Kunsthall Stavanger is proud to present Bleak House, the first exhibition in Norway by artist-duo Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings. Featuring an installation of 15 found dollhouses and a multi-channel sound piece, as well as a selection of original etchings and a video work, the exhibition highlights the relationship between architecture and the construction of identity, power dynamics and societal norms.

Quinlan and Hastings are London-based multidisciplinary artists working across painting, drawing, video, performance and installation. Their practice is grounded in researching how various communities have been represented at different moments in history as they look to art history and archives to interpret social and political issues facing us today. Amongst other things, they have studied queer environments, explored the impact of austerity, gentrification and policing on urban spaces, and investigated the more overlooked facets of western feminism, particularly its relationship to the political right. Through their work, the artists unpack the various forms of authority, power and disorder within our public spaces and question how social hierarchy, class and obedience are negotiated.

The exhibition at Kunsthall Stavanger focuses on the concept of the home from a queer feminist standpoint, and offers differing perspectives on the domestic sphere as a place of power and oppression. The artworks presented in Bleak House reveal how societal ideals are encoded in the environments we build, and reveal the structures that perpetuate these strictures. The exhibition takes its title from the eponymous novel by Charles Dickens in which a Victorian manor serves as the setting for a complex familial, legal, and relational drama, and the emotional quality of the literary work sets the tone for the installation.

Bleak House centers around the installation Inside, which consists of 15 found dollhouses, displayed on metal plinths like sculptures or museum relics. Over a century of British domestic architecture is reflected in the design of the dollhouses, with a focus on the Victorian era. Dollhouses emerged from Northern Europe in the 17th century as markers of social class. Rather than objects of imagination and play, they were originally intended for display and pedagogy. Dollhouses, or “miniature houses'', were often replicas of the owner’s own home and showcased their wealth while simultaneously instructing young girls on the upkeep of a household, including its servants. During the Industrial Revolution, mass-produced dollhouses entered the toy market, but the ideals of class, gender, and society in which the original dollhouses were rooted remained. Artist and anthropologist Louise Krasniewicz reframes dollhouses, stating that they are not just down-sized objects, but world-makers. In Miniature Manifesto, she writes that dollhouses are “not an escape from the real world but a way to engage, confront, question, critique, or consider it.”

In Inside, Quinlan & Hastings challenge the domestic ideal of the wealthy, white, western, heteronormative, single-family home. The empty dollhouses have become eerie rather than playful – a miniature ghost town – while a soundtrack animates the barren structures. Within each dollhouse, a speaker emits a looping 50-minute sound piece of found and original material by composer Owen Pratt. The sounds, at times synchronous, at times disjointed, allude to the infinite psychological potential of a house. The installation confronts our earliest indoctrinations into domestic life, and critically considers how the built environment can reinforce or re-imagine our societal expectations. Inside is accompanied by a commissioned text by artist and writer Huw Lemmey on the role of the British suburban house and its impact on feminist and queer life, and a poem by artist Rene Matić.

In the side galleries, the concepts undergirding Inside are expanded to include the complex intersections of feminism and the political right. In one gallery, a series of twelve original etchings collectively titled Disgrace complicate the feminist narrative by revealing the entanglement of feminism with the political right, specifically in the UK. Here, the artists reveal the same ideals of class, gender, and society encoded in the dollhouses by presenting specific moments in history where feminism became entwined with the violence and oppression of colonialism and capitalist interests.

The timeline starts with Imperial Ladies Auxiliary and Tea, garden & evening parties, rifle competitions, polo matches, the trooping of the colours and other special events, which illustrate the role of women in the British imperial project in the late 1800s. Votes for Ladies exposes the Women’s Suffrage Movement’s affiliation with conservative ideologies such as the Women’s Social and Political Union, which advocated for suffrage for female property owners instead of universal suffrage, while Women’s Police Volunteers highlights women’s complicity in oppressive policing practices. Social Hygiene shines a light on the Eugenics Movement of the early 1900s, and Blackshirts presents how many suffragettes in the 1930s and 1940s were in league with the British Union of Fascists. The etching Sex Wars depicts a clash between sex-positive campaigners and anti-pornography feminists in the 1980s, touching on a period in which anti-sex work campaigners identified women as objects of oppression in need of protection, regardless of whether protection was wanted.

Free-market Feminism compares the effects of ‘corporate feminism’ to an etching from Goya’s series The Disasters of War, while Empire cake illustrates a recipe promoted by British women that perpetuated imperial mindsets through the domestic activity of baking. Gatekeeper depicts one woman controlling the terms of feminism, effectively deciding who gets to be a feminist, and how. The timeline ends with the etchings I’m not a woman I’m a conservative and We Will Not Be Silenced, which focus on Conservative groups such as Women2Win that aim to increase the number of Conservative women in government, and TERFs (Trans-Exclusionary Feminists). Though the scenes depicted in Disgrace refer to a specific British history, they exemplify how we might interrogate the feminist rhetoric within our own local, regional, and national settings.

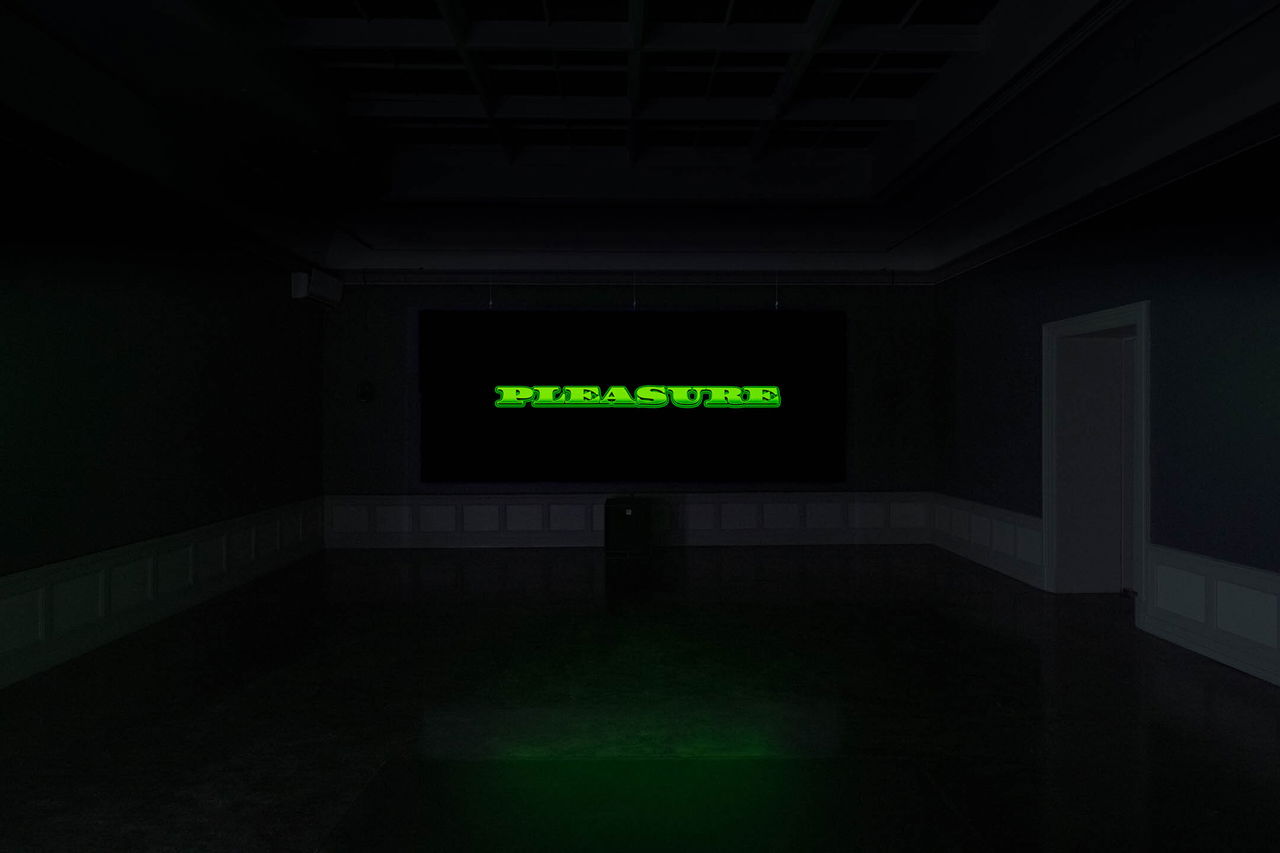

The video work Everything Is Folly In This World That Does Not Give Us Pleasure is composed of text and found footage of LGBTQ+ people dancing in their homes, by themselves, for themselves. The title is a translation of a line from “Brindisi”, a traditional Italian drinking song and an opening scene from the opera "La Traviata,” and encourages the characters to drink and toast to life, joy and pleasure. The inclusion of the video at Kunsthall Stavanger shows queer dance as a joyful and defiant reclamation of domestic space.

The exhibition at Kunsthall Stavanger reveals how societal ideals are embedded in our physical and political structures. Within the context of Stavanger, with its ongoing debates around economy, housing, historic preservation, new construction, and the increase of conservative politics, the artworks in Bleak House ask us to consider what family structures, societal goals, and political ideologies are mixed into the mortar of our surrounding architecture. The exhibition tells a history of norms and fantasies about family life, gender, power, and sexuality, and points towards joyful ways we can individually and collectively imagine an alternative future.

Curators: Hanne Mugaas and Heather Jones

Exhibition text: Heather Jones

Exhibition technicians: Matt Bryans, Owen Pratt, Leif Ole Stampa

Sound design: Owen Pratt

The exhibition is generously supported by Fritt Ord and Norske Kunstforeninger.

Kunsthall Stavanger would like to thank the artists, Hekátē Studios, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi and Arcadia Missa Gallery.

Photo credits: Erik Sæter Jørgensen and David Stjernholm.

Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings (b. 1991, Newcastle and London) are a London-based artist duo whose work encompasses painting, drawing, video, performance, publishing and installation. They had a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in 2022-23, and received The Jarman Award for Emerging Film Artists in 2020. They have exhibited internationally at Kunsthalle Osnabrück (2022) and Isabella Bortolozzi (2020) in Germany, Whitechapel Gallery (2020) and Arcadia Missa (2021) in London, MOSTYN (2020) in Llandudno, Wales and Pinchuk Art Center (2021) in Kyiv, Ukraine, among others.

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023). Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023). Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: David Stjernholm

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023). Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: David Stjernholm

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023). Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings, Bleak House (2023), Installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger. Photo: Erik Sæter Jørgensen