Systema Naturae, developed for Kunsthall Stavanger by independent curator Mirja Majevski, brings together the work of six contemporary artists: Ann Böttcher, Sanna Kannisto, Eva-Fiore Kovacovsky, Kustaa Saksi, Salla Tykkä, and Michael John Whelan. Rooted in botany, the international group exhibition sets out to contemplate humankind’s relationship to nature.

The exhibition borrows its name from a book first published in 1735 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linné (Linneus). The publication, together with other volumes by Linné, came to play a pivotal role in the establishment of universally accepted conventions for the naming of organisms. The Linnaean system, being the first one to methodically use binomial nomenclature, epitomized the far-reaching aspirations of the European plant sciences that were coming of age during the eighteenth century. During this time, as the European colonial empire expanded and generated a vast influx of new specimens, the elite scientific community raced to establish a system that

Systema Naturae, developed for Kunsthall Stavanger by independent curator Mirja Majevski, brings together the work of six contemporary artists: Ann Böttcher, Sanna Kannisto, Eva-Fiore Kovacovsky, Kustaa Saksi, Salla Tykkä, and Michael John Whelan. Rooted in botany, the international group exhibition sets out to contemplate humankind’s relationship to nature.

The exhibition borrows its name from a book first published in 1735 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linné (Linneus). The publication, together with other volumes by Linné, came to play a pivotal role in the establishment of universally accepted conventions for the naming of organisms. The Linnaean system, being the first one to methodically use binomial nomenclature, epitomized the far-reaching aspirations of the European plant sciences that were coming of age during the eighteenth century. During this time, as the European colonial empire expanded and generated a vast influx of new specimens, the elite scientific community raced to establish a system that could accurately describe and consistently catalogue all of the plants in the world. Imagine if another way of organizing and naming would have prevailed over the Linnaean system – would we now see the world differently?

While displaying their distinctive ways of interpreting and relating to the natural world, the artworks featured in the exhibition also allude to historical modes of organizing and conveying information about natural flora, thus piecing together a fragmentary history of botany.

In her intricate pencil drawings of trees, Ann Böttcher explores the cultural construction of nature. Her Dürer-like study of a miniature Norway spruce, Picea abies ‘Mariae-Orffae’ (2016), subtly questions the interrelation among national identity and landscape.

During her career, Sanna Kannisto has made several trips to the tropical rainforests in Brazil, French Guyana, and Costa Rica. Positioned in the field stations of biologists, and using materials close at hand, Kannisto has undertaken visual research that enquire into the photographic gaze and the claim for universality and objectivity that the sciences pose.

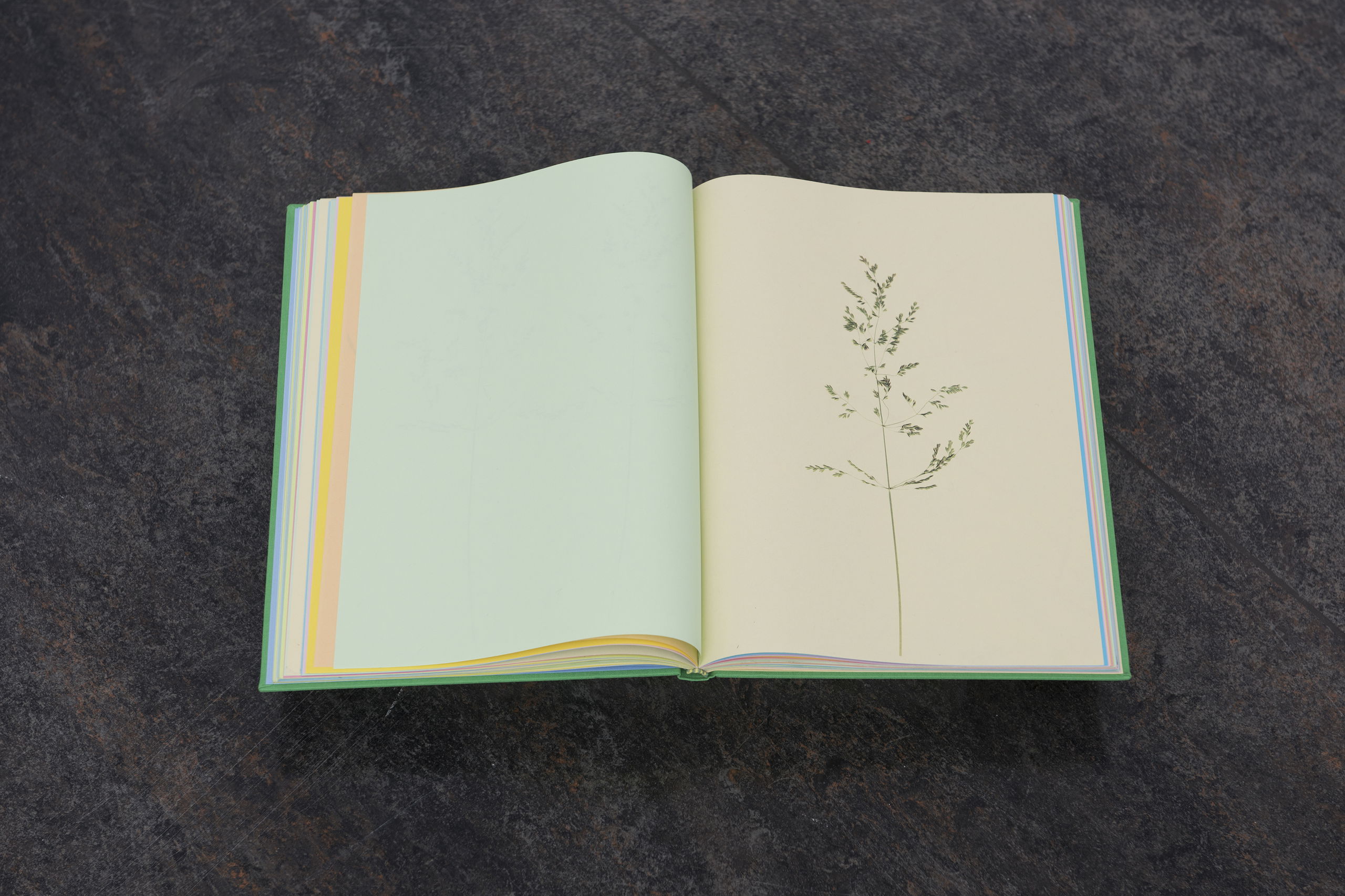

Working intuitively in a darkroom, Eva-Fiore Kovacovsky places dried and pressed samples of perforated foliage into a negative holder of an analogue enlarger and repeatedly exposes them though color filters, creating her photograms. Further, Kovacovsky’s 274 Gräser (2010) is a hardback book of unique inkjet photocopies of pressed plant specimens exhibited on top of a recent reprint of Hortus Eystettensis, a book that transfigured botanical art when it was first published in 1613.

Kustaa Saksi’s sizeable jacquard loom tapestries borrow freely from shapes and patterns of flora and fauna. Like early botanical illustrations, they engage the observer in a hypnotizing play of forms and colors, such that the distinction between fantasy and verity is rendered incidental.

Salla Tykkä’s Victoria (2008) portrays the nocturnal bloom of a giant water lily, a native of tropical South America. Europeans first sighted the plant in the early nineteenth century and eventually, in 1837, named the genus in honor of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Consequently the plant became an emblem of the new monarch whose colonial empire stretched throughout the world.

The photographic series In the black dark for good (2016) by Michael John Whelan is a study of stones outside the entrance of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which are covered by freezing liquid ejected by the vault's cooling system. On show will also be the installation Chamber (2016–) that consists of a field recording from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, alongside a printed inventory of it’s contents and an empty sheet signifying future prospects.

Systema Naturae is realized with the kind support of Culture Ireland, Pro Helvetia, Frame Contemporary Art Finland, and the Finnish-Norwegian Cultural Institute.

Thanks to Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm; Gallery Grey Noise, Dubai; STAMPA Galerie, Basel; Stavanger Botanic Garden; and all the others who helped realize the exhibition.