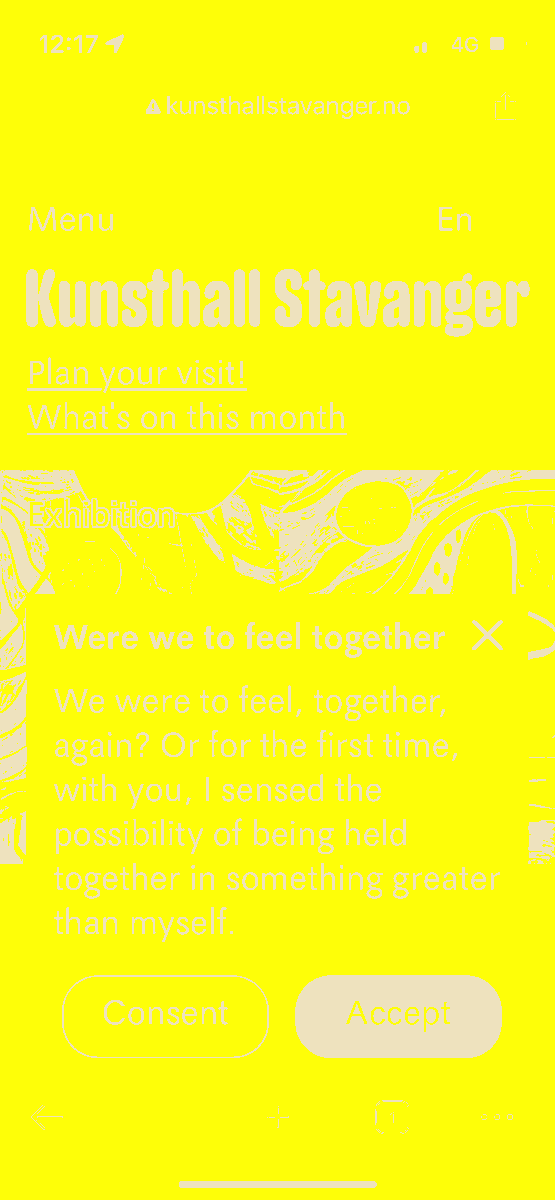

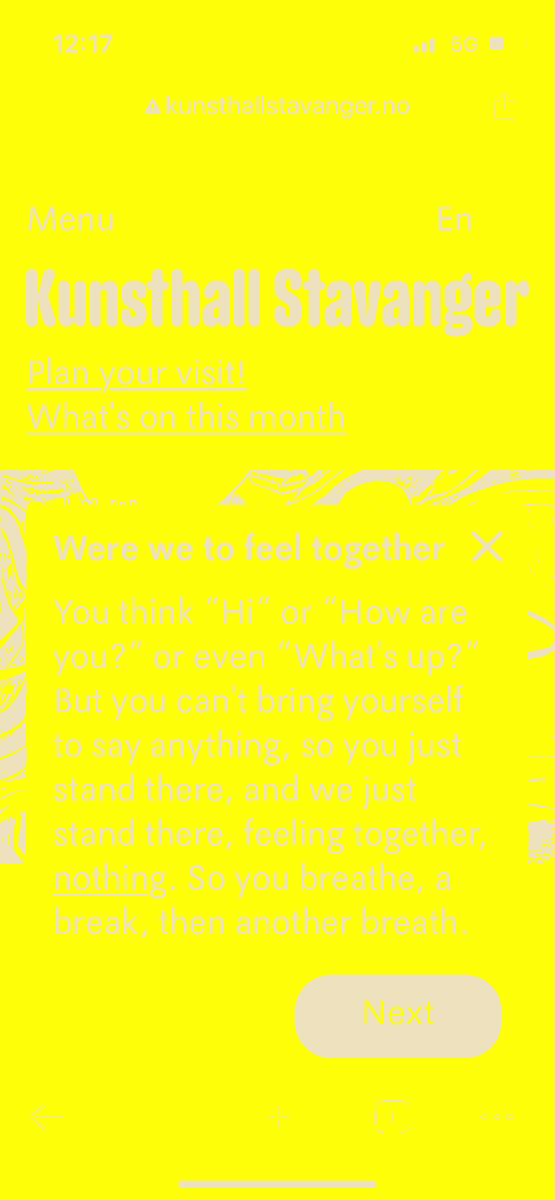

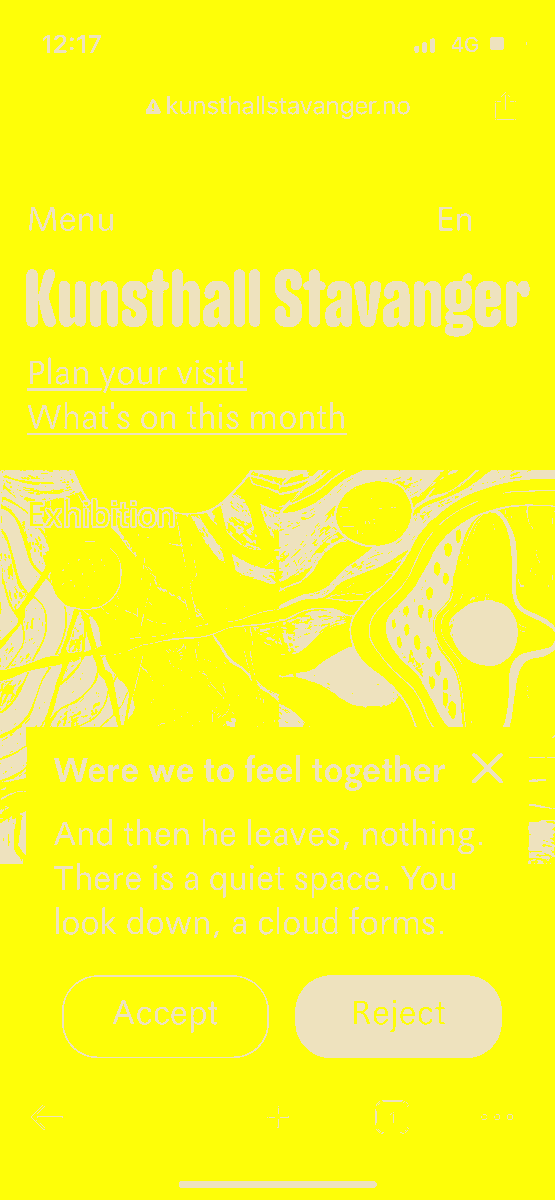

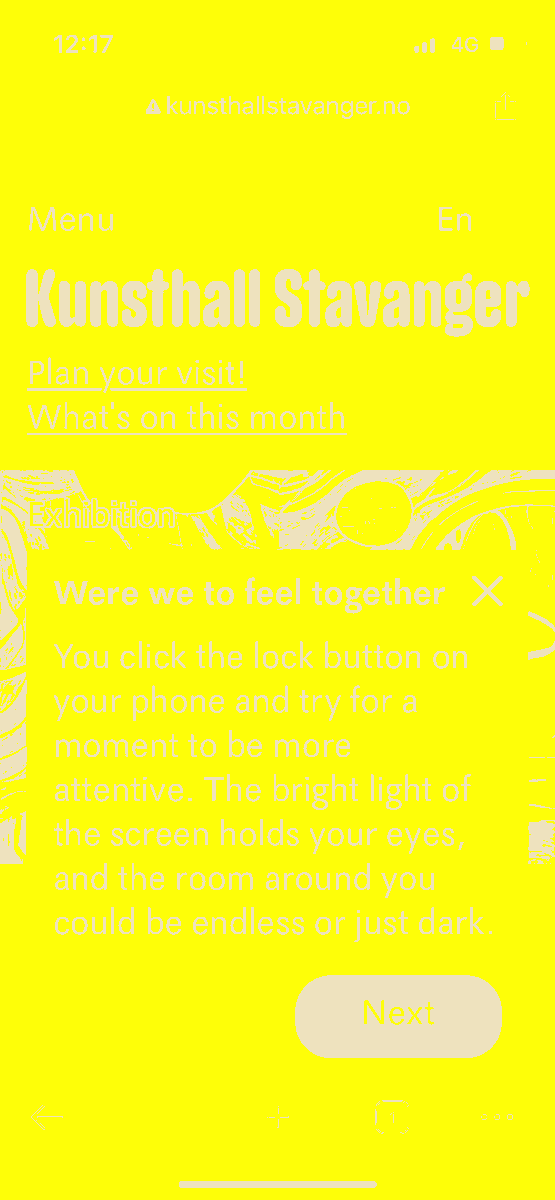

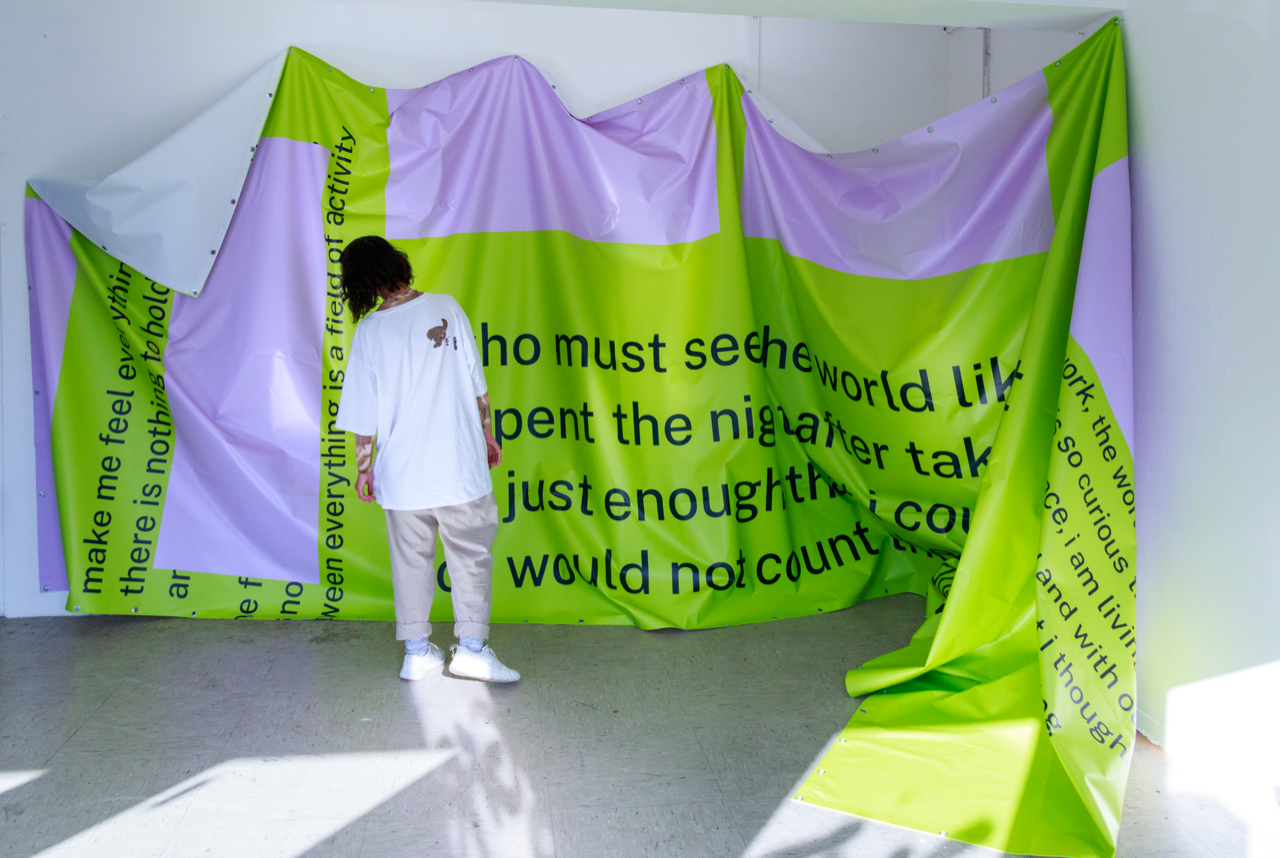

Were we to feel together is a commissioned work that is part of the project Even When We Can’t We Must, honouring Norway’s Queer Culture year. For the duration of the project period, virgil b/g taylor’s work was available for visitors to interact with on Kunsthall Stavanger’s website. Working with the format of a hypertext poem in the form of a cookie banner, taylor looked closer at ideas of consent both when we navigate online and how the concept has been activated in law, specifically in connection to queer histories. Below follows a conversation between virgil b/g taylor and Curator Kristina Ketola Bore. Images and a video documenting the work can be seen in the media section on this page.

Kristina Ketola Bore: This work is the third in a series of digital projects titled Even When We Can’t We Must that Kunsthall Stavanger has initiated as part

Were we to feel together is a commissioned work that is part of the project Even When We Can’t We Must, honouring Norway’s Queer Culture year. For the duration of the project period, virgil b/g taylor’s work was available for visitors to interact with on Kunsthall Stavanger’s website. Working with the format of a hypertext poem in the form of a cookie banner, taylor looked closer at ideas of consent both when we navigate online and how the concept has been activated in law, specifically in connection to queer histories. Below follows a conversation between virgil b/g taylor and Curator Kristina Ketola Bore. Images and a video documenting the work can be seen in the media section on this page.

Kristina Ketola Bore: This work is the third in a series of digital projects titled Even When We Can’t We Must that Kunsthall Stavanger has initiated as part of Queer Culture Year in Norway. In 2022, Norway commemorated 50 years since the abolition of a law that stated that sexual interaction between men was forbidden. Effectively, the termination of this law decriminalised the act of being gay in Norway.

For this project, I have invited artists who use text in different ways, often in performative ways, to create new works for our digital platform. My interest in language stems from the power of text and language in queer activism, for example through art and design, protest and oral history. What was your initial response when invited to this project?

virgil b/g taylor: There is always a risk in celebrating the achievement of tolerance by the state, as is the case in this anniversary, but I think, or hope, that attention to the history of the law is importantly a manner of paying attention to the history of language, as the law resides in that register—a set of words and phrases that seek to make the world conform to a certain idea—backed by the state’s monopoly on violence. Though this work is centred on a place less familiar to me, I was heartened to learn that your interest, like mine, was rooted in something more like the meaning and impact of these sort of legal transformations of certain categories of life and behaviour.

KKB: In the process of creating this work, we had several conversations about the idea of consent and what that can mean in the perspective of queer histories. You have also previously worked on queer histories in connection to the law. Could you say a bit about how you worked with these concepts and how it transformed into the final work we see on the website?

vbgt: I find it difficult in my work and research to distinguish between queer history and the history of the law. Sexuality as such, in whatever orientation, cannot be spoken of without escaping the law, the state having taken up a description of difference and making it material by legislating its exclusion. This isn’t to say that queerness doesn’t exist or is merely a legal question; rather, because of the history of various states imposing such laws, we cannot speak of ourselves without escaping the long shadow of the law. I think about the work of scholars like Ian Hacking who traces the process of a dynamic nominalism wherein the described take on the description and reinvent its possibilities. When states like Norway liberalise their approach to homosexuality, they produce new categories of being, in which men who have sex with men might imagine new horizons for life, or be subsumed into the fantasies of inclusion that are offered by these reforms.

The question of permission to have sex has much to do with the idea of consent, that the agreement between the parties through an (informal) verbal contract to consent to the activity is what makes that activity acceptable. While this is certainly good—without consent there is only violation—the necessarily legalist form of “consent” that is extended into all aspects of life creates a diminished capacity for understanding what is mutual, what is felt and what is understood. It also demands a fantasy of an autonomous subject, whose consent is abstracted from all the other things in life that might inform the offer. The law addresses individuals as merely that, distinguished by their relationship to the state through categories like citizen, immigrant, child, foreigner. These lonely categories hold us apart, wrapping us into fictions of rationality and responsibility. No one is truly autonomous, and no choice is made without context. Consent in one moment depends on that moment, that place, that circumstance. Queer people’s history of having to advocate for our own right to consent to the kind of sex we desire makes clear the contingency of our autonomy.

The work I do today is informed by my experience working with and in the collective What Would An HIV Doula Do?, “a community of people joined in response to the ongoing AIDS crisis”, whose collective engagement with the ongoing HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics materially situates all struggles for justice as collective and co-constitutive. Queerness, or even homosexuality, is just one axis of that struggle, and as queer person it is often this axis in which I feel the most possibility for me to express an engagement in that larger struggle. In that sense, I hope that the work I make is not merely queer, but rather engaged in examining those horizons offered by enlivening these contingent categories of being.

In this work, responding to the constant demand to consent to the exchange of identifying information in order to use websites like https://kunsthallstavanger.no/, I offer that even this most mundane act of consent is intimately linked to the struggle to be more than just mere autonomous subjects, but rather in exploring the collective and contextualised nature of all our actions I’d like to find something other than just life as a mere agent. I don’t know if this little hypertext poem can achieve that, and I worry that articulating such a grand promise for such a small gesture might collapse the possibility of it doing this work. But I think it’s nice to try.

KKB: Your work seems to tell us about our own acts of creating distance while striving to build closeness when we engage with each other online, and how online engagement also can create fear of closeness. At the same time the form you have given the work manages to show us how that interaction works. What was the appeal for you to work with the concept of flow questionnaires? What do you think it can tell us about the way we interact online today?

vbgt: I think that distance comes from the material reality of the fiction of autonomy described above. When we are made to understand ourselves as acting alone, we feel alone. And it is a cruel loneliness that inserts itself into moments of coming together. I chose this flow questionnaire format as a call back to the hypertext writing formats which preceded the world wide web or the Choose Your Own Adventure novels which I felt like I missed out on when I was younger. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun’s work is a touchstone for me in my approach to the digital/online world—she helps us see that nothing is ever really new in the “digital world”, that we are always “updating to remain the same”, all that is new is a shimmering illusion, as the violence of the “real world” is reproduced in the literary fictions of “new” media. I find it really compelling to look back at not only early internet forms but also early writing on the internet, where you see this repetition so clearly.

Christina Sharpe, in a 1999 essay entitled “Racialized Fantasies on the Internet”, brilliantly brings together many early examples of the kind of exclusion with which many online spaces and platforms still notably struggle. In opening the essay with Essex Hemphill’s contribution to a 1995 conference at the City University of New York wherein Hemphill wonders, nearly thirty years ago: “is it possible that I am unwelcome here, too?”, Sharpe reminds us that these apparently new spaces have always been merely novel forms of the world before us, updating to remain the same from the start. Hemphill’s interrogation of the nascent online invokes his lived experience as a person with AIDS, and thus he finds himself “counting T-cells on the shores of cyberspace and feeling some despair”—that this world of immediacy and promised networked presence is actually one of distance and despair.

KKB: The text that is part of building up the work feels both intimate but also very relatable. Throughout some words appear: Consent, Allow, Break, Reject, Accept. I think these are words and concepts that many who engage online can recognise from their own actions and their reflections of online existence. They also mirror collective conversations about online presence, but somehow the work manages to poke a bit deeper – perhaps because it seems to have this undercurrent of passion and the fear of rejection. How did you identify these words in the process of writing the work?

vbgt: In my Fag Tips Utopia Zine or in grids of sketches I post on instagram, I find that I often return to this post-break-up, horny, lonely voice, an unfixed wandering mix of longing and regret, and lots of “I” and “you” rolling together. It is kind of a pathetic but ultimately familiar tone, not too challenging to put myself in the mind to write with, and captures something of the dialectic of two persistent online vibes: fomo and u ok? Both fomo and u ok? necessitate a distance of the speaker from the action, in missing and inquiring the speaker is not experiencing. Between the jealousy of fomo and the recoiling of u ok? is the desire to feel as another or to feel the other, or simply, to be with an other. But online we navigate this feeling through the clunky algorithmic writing of mostly men in California who profit-seek in the waves of our attention. Thus we are reduced to those familiar words you mention. These clunky computer and legal metaphors make sharp corners of our ambiguous and flowy desire. Between these insufficient markers remains those still material, still embodied feelings of passion and fear of rejection. I think we feel online these words as minor paper cuts, making our desires failed volleys into the voids that are inserted by disorienting algorithms between, rather against, us. Failing our desires can have the taste of achieving them, there is a pleasure in having something withheld. So as much as I lament the apps, or the unfulfilling night at the club, there is still some memory of pleasure in those disappointments. In each u ok? the glimmer of desire to feel something, to not miss out.

KKB: In your work you sometimes bend language, making it slightly opaque or just a little bit perplexing. What do you hope will happen in that space between receiver and work when you add in this little disruption in our reading and listening experience? This method is also deployed in the title of this work, Were we to feel together, yet the title also gives us a sense of poetry and an openness for interpretation. Could you say a bit about what the title means to you?

vbgt: I have tried to write more closely to the register of speech, where grammar and the meaning of words fall away to what feels right, or taken at a distance might point to where I could not write. At best it is a chance to work with the reader/viewer, to make meaning together but that seems a bit lofty!

The title is a play on the word consent, to feel together, a legal term I have been working with in recent projects. Unlike the register of speech, the legal register demands a difficult and exclusive specificity. But consent, as a term, has had a leaky journey from the law into our everyday language, especially in regards to how we articulate our boundaries. In recent years, with the rise of data protection laws like the General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union and European Economic Area countries like Norway, we are asked to consent to cookies and other trackers. Many users quickly click accept or consent, those tricky words from your previous question, without much thought. Other users routinely reject these same trackers with the same impulsive speed. Were we to feel together does not pretend to offer a critique of those data laws or offer solutions to the constant demand for our data, but rather to reflect on that action of consent and to weave the unsexy cookie dialogues back together to the other questions of consent that arise in more intimate encounters.

Curator: Kristina Ketola Bore

Developer: Bryant Wells

The year 2022 marked the 50th anniversary of the repeal of a law that prohibited sexual acts between men 50 years ago, effectively decriminalising being gay in Norway.

Kunsthall Stavanger honours Queer Culture Year with a digital project consisting of four commissioned works by Nat Pyper, Olivia Douglass, virgil b/g taylor and Zutana Hadaddeen. The works are presented as interactive projects on our digital platform, with the first launching in December 2022, and the others following in March, May and September 2023.

The title for the project, Even When We Can't We Must, is borrowed from a work by Nat Pyper bearing the same name.

virgil b/g taylor is a faggot, living in Germany. He makes fag tips, an online speculative zine. He is one half of sssssssssSsss, a study-friendship with Ashkan Sepahvand, a third of Indefinite Leave to Remain with Moad Musbahi and Vishal Kumaraswamy, and a fraction of What Would An HIV Doula Do?, a collective of artists, writers, caretakers, activists and more gathered in response to the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic. His work explores histories of care, crisis, exclusion, and toxicity.